To mark the 25th anniversary of my long-running pop-culture blog, Pop Candy, I’ve been looking back on that era with a series of essays. Today’s piece is part of a larger project.

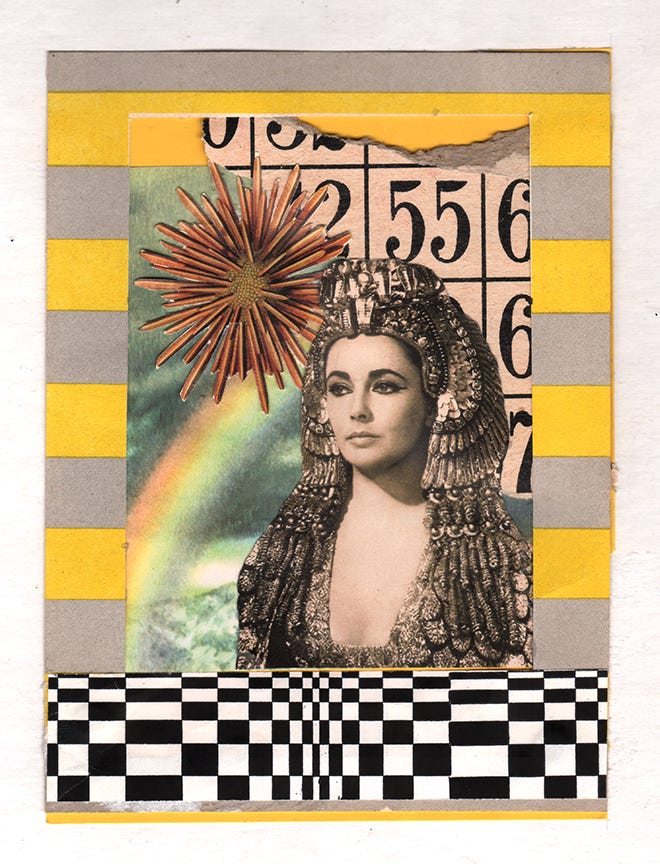

Huge thanks to Marlene Weisman for creating this week’s art! See more of Marlene’s collage work on Instagram and at marleneweisman.com. She’s one of my favorite artists (and people).

Seven years before Elizabeth Taylor died, I began working on her obituary.

That’s not unusual: Most news organizations hold obits for years and years, so when the time finally comes, they can just insert age/date/cause of death and – click! – start spreading the bad news.

With Liz, I was asked to make a photo gallery of her life and career. I had gobs of material – the fragrances alone could fill a barn – so the project wouldn’t be quick. But it was important, and rumor had it she wasn’t in great health, so I got to work.

Death has always moved papers and raised ratings, so naturally, it did big business on the internet. When Ronald Reagan died in 2004, funeral updates, think pieces, audio reports, photo galleries, live chats, and video clips racked up millions of pageviews. Going forward, plain text obits no longer sufficed on the web, which is why I was suddenly cropping photos of Husbands #1-8 on my lunch breaks.

As appetites for news swelled online – and it became clear that death and awards shows could yield hefty ad dollars – I watched colleagues build grand multimedia memorials of still-living notables like Pope John Paul II, Queen Elizabeth, Jimmy Carter and Muhammad Ali. The next time a Reagan-sized event hit the news cycle, we’d be ready with the biggest, best black celebration of them all. So … go, team?

The first obituary I ever wrote was for James Earl Ray, the man convicted of assassinating Martin Luther King, Jr. Once again, he wasn’t dead at the time – it was an assignment from one of my college professors, who expected most of us to work for small local newspapers after graduation. “You’ll probably start out in obits or the police beat, but don’t complain,” he told us. “It’s invaluable experience, and since everyone reads those pages, your byline will be seen by the whole town!”

After I graduated, I jumped straight to a national paper, where I was hired for a job that didn’t exist a couple years earlier: working in HTML and making updates to the website on the overnight shift.

One night in the newsroom, a report came across the wire of a small plane that had crashed into the Atlantic Ocean off Martha’s Vineyard. It was piloted by John F. Kennedy Jr., with his wife, Carolyn; and her sister, Lauren, as passengers.

There was no time for emotion as reporters and editors moved through the process that had become muscle memory: making calls to confirm the deaths, writing a headline, selecting photos, asking each other to backread and copyedit. Watching them work, I felt like medical student John Carter in the pilot of ER, a nervous neophyte who keeps getting in the way. I did what I was told and tried to soak up the rest.

As years passed, I, too, grew accustomed to covering celebrity deaths. (A handful disrupted our mechanical routine: When Heath Ledger died, gasps erupted across the newsroom. Zero outlets had that obit on file.)

When you write about other people’s legacies, you can’t help but consider your own. Have I already done the things I’ll be remembered for? Are they different from how I’d like to be remembered? The older I get, the more I’m aware my time is limited. Which stories are the most important for me to tell? What are the things I most want to do, where are the places I most want to go? These days I feel more like ER’s Nurse Hathaway, constantly performing existential triage on my own life.

An obituary is a permanent record of one’s time on Earth – sometimes the only such record, which is why it’s disconcerting that there are far fewer people writing them than when I began. Since 2005, we’ve lost one-third of newspapers and two-thirds of newspaper journalists in the U.S. Many small areas, particularly rural and poor ones, have one or zero local news sources. Giant corporations are buying and devouring small, independent media outlets, churning them into cookie-cutter versions of each other with the same repurposed stories on every website and printed page (where that still exists).

Big names will always be memorialized – if, for no other reason, that they’ll earn clicks and cents for the companies that write the headlines. But what happens to the rest of us? If we die and no one writes our obituary, did we even live at all?

Elizabeth Taylor died on March 23, 2011. Many publications ran obits they’d been holding for years, including The New York Times, which published a lovely remembrance written by film and theater critic Mel Gussow. Unfortunately, Mel never saw it in print, because he died in 2005.

As for the photo gallery I spent weeks crafting, it was never published, because the software I’d used had become obsolete by then. My work was easily replaced with a faster, better, newer product. It wouldn’t be the last time.

Such is life.

More essays in this series: Andy Warhol | The Red Carpet | LOST

That's fascinating. Especially the part about an obit written by a dead person!